Discover more from The Trip Report by Beckley Waves

What if the 'Psilocybin vs. Escitalopram' trial used Digital Biomarkers to measure results?

Welcome to "Late-Stage" DSM categorization of mental disorders

Quick Summary

Milestone trial results published in NEJM comparing psilocybin to the antidepressant escitalopram for the first time

Paradoxically, results are both inconclusive and favor psilocybin over Escitalopram in the treatment of depression.

How we “measure” “depression” in research is fundamentally flawed

The psychedelic renaissance is coinciding with fundamental changes in the measurement and classification of mental disorders

Digital Biomarkers will replace multiple-choice surveys as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) overtakes the DSM and psychedelics1 overtake the antidepressants.

Last week, Robin Carhart-Harris and co-authors published the results of the first head-to-head comparison of psilocybin vs. an antidepressant in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine.

The most common impressions/comments/takeaways:

Bravo! A well-done, first-of-its-kind comparison trial of psilocybin and Escitalopram. Kudos to the authors. A milestone for the field.

The study was inconclusive2 because it was underpowered3. The primary outcome measure, the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Report (QIDS-SR-16), revealed that patients in both groups improved, the psilocybin group improved more, but not enough to be considered clinically significant.

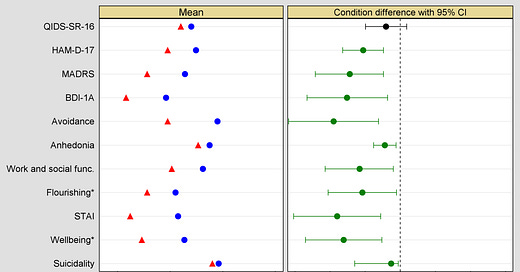

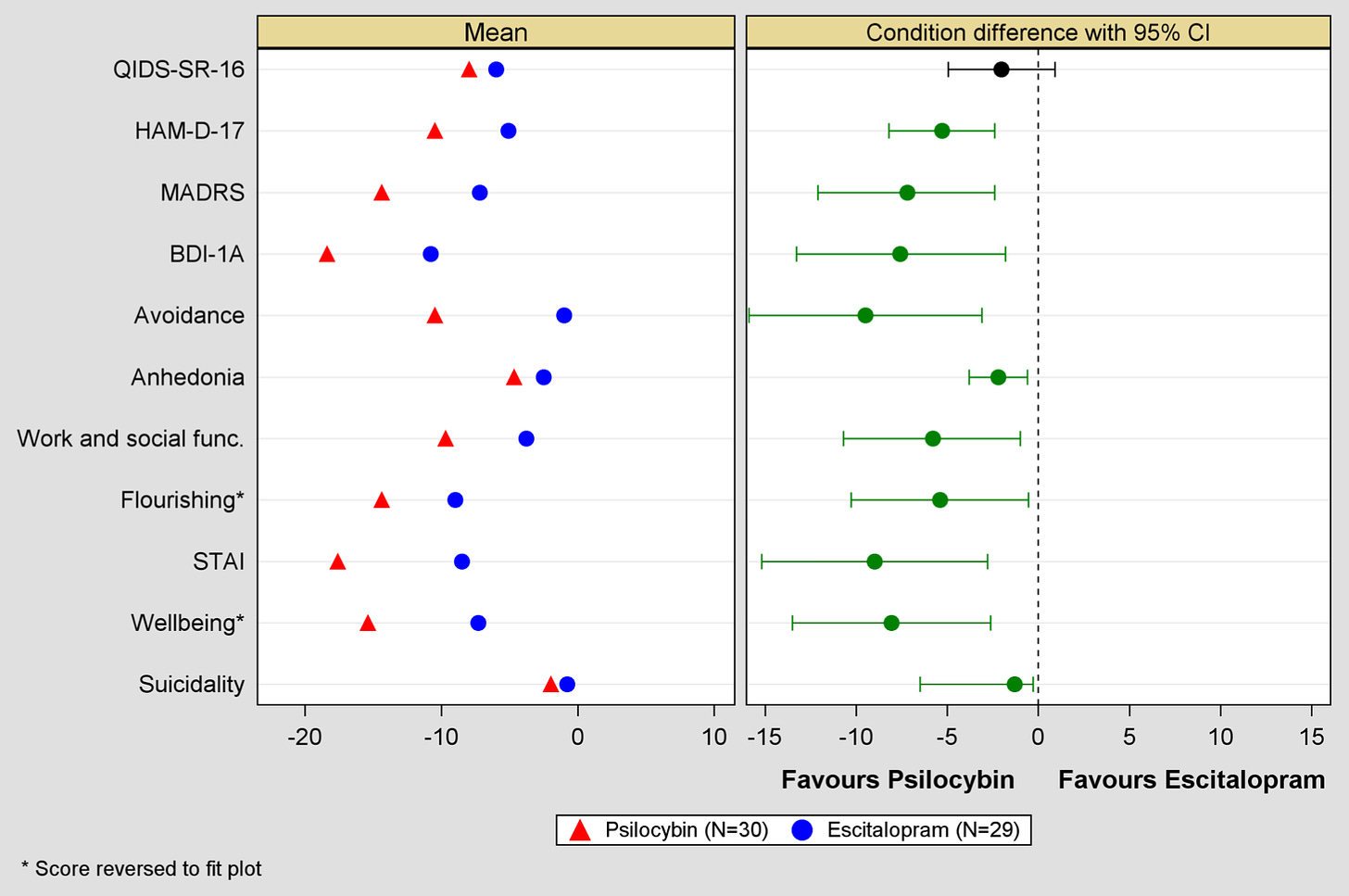

The real results are in the secondary outcomes—all of which favored psilocybin.

Call your shot before you shoot your shot

Good science requires that you declare what you are going to do and how you will measure it, before you do it.

It is like a game of horse; you have to call your shot before you shoot. If you call “bank shot4” and your shot doesn’t hit the backboard but still goes in, it doesn’t count.

In this case, the Imperial team called their shot when they decided to use the QIDS-SR-16 as the primary outcome.

They also used other measurements, secondary outcome measures, which are useful, offer additional insight, and will help inform future trial design. Still, since you can only have one primary outcome measure, they don’t “count” when officially drawing conclusions.

As lead author, Robin Carhart-Harris lamented, the choice was almost arbitrary:

“This study used multiple depression measures (QIDS-SR-16, HAM-D, MADRS, BDI-1A) among which QIDS was defined as primary, a largely arbitrary choice, and in hindsight, not a good one. This was the only outcome measure where the psilocybin vs SSRI difference was not statistically significant. It was significant on all of the other depression measures!”

"in saying no conclusions can be drawn on the secondary outcomes due to the absence of correction for multiple testing, we are recognizing the risk of false positives when casting a wide ‘fishing net’. However, when one factor in how consistently the secondary outcomes favoured psilocybin and by what margin, it is easy to suspect that the miss on the primary outcome is in fact a ‘false negative.’”

Here is a graph of the secondary outcomes Dr. Carhart-Harris refers to, showing psilocybin superior in virtually all categories.

In other words, we have a situation in which the researchers were like a guy chosen from the crowd to shoot a full-court shot at halftime of an NBA game for a million dollars—but he has to call his shot. Thinking a 90-foot hurl has a better chance of going in off the backboard, he calls “bank shot” only to throw up the shot of his life that goes in perfectly, nothing but net.

Doesn’t count.

Then I saw this from Boris Heifets:

“The inconclusive outcome may say more about a generation of psychiatric scales designed for SSRIs than it does about psychedelic potential”

Dr. Heifets’ offered more insight via the excellent write up from Psilocybin Alpha:

"It’s more likely than not that existing metrics for depression are just not well suited to studying psilocybin and measuring its impact, e.g. emotional breakthroughs, meaning-making, spirituality. Hopefully, the field will evolve and broaden its horizons."

I started wondering, “How do we measure depression?”

Which lead me to, “What is depression? How do we define it? How can a subjective experience possibly be objectively quantified? Am I depressed?”

Which, of course, eventually leads to the question of “what does it mean to be conscious and sentient?”

The slide from asking "How is depression measured?" to "What does it all mean and why am I here?" is well oiled. Before we build up too much speed down this slipperiest of slopes let's actually look at how psychiatry/psychology researchers "measure" "depression" and how that will be changing.

Depression, Measured

Do you know how psychology, psychiatry, and mental health researchers measure depression?

With surveys.

Self-rated, multiple-choice questionnaires5.

At a time when we have a global, anonymous, peer-to-peer digital currency with a $1 trillion market cap; when the rockets used to launch space shuttles into orbit are returned to earth with pinpoint precision, when waste carbon dioxide can be removed from the atmosphere—we are still using multiple-choice surveys to measure mental health conditions6.

DSM Based Surveys

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a universally loathed artifact of psychiatry’s attempts to quantify and qualify subjective human suffering. It seems to be universally loathed for reasons related to reimbursement, big pharma, big healthcare, and Rene Descartes.

Psychiatrist & writer Scott Siskind:

“Remember, the DSM is fundamentally a diagnostic guide. It’s a list of criteria to determine who has eg depression. To oversimplify just a little, if a patient has five or more of their depression criteria, then they “really have” depression, and a psychiatrist should diagnose them. If they only meet four or fewer, they don’t have depression, and should not get the diagnosis. All of this is predicated on the idea that there’s a specific thing called depression that you either do or don’t have.”

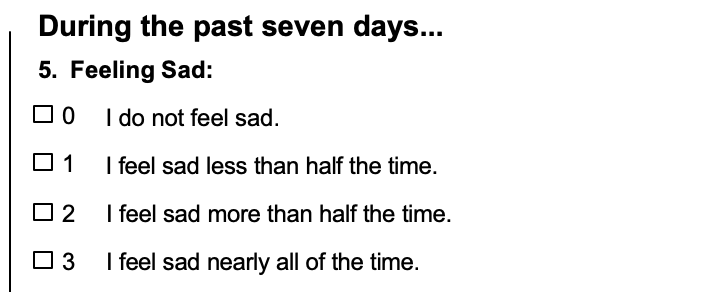

The primary outcome measure of the psilocybin vs. Escitalopram study was the QIDS-SR-16. This is a self-rated, multiple-choice survey composed of 16 items that correlate with the DSM-IV symptom criteria for depression.

Below is an example of the type of questions the QIDS-SR-16 asks and the four response choices:

The other 15 multiple choice questions ask for similar ratings about sleep, appetite, restlessness, and the subjective feelings of weight gain or weight loss, concentration, energy, restlessness, suicidal thoughts, and interest levels7.

A similar survey used as a secondary outcome measure is Beck’s Depression Inventory. Beck’s is a 21 question, multiple-choice survey very similar to the QIDS. Another is the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, again with similar questions, presented with multiple choice answers.

All of these surveys are meant to identify symptoms that, when present in sufficient quantity and intensity, create the experince we call depression.

This is by no means a critique of the researchers or their study design choices. There are constraints and considerations, measurement processes need validation, and it seems there are no good options.

But isn’t it telling that potentially paradigm breaking research on the leading cause of disability worldwide is resigned to using paper and pencil surveys to measure outcomes while we are all walking around with supercomputers in our pockets?

Supercomputers that can collect the very phenomena these surveys seek to capture— mood, behavior, activity, sleep, word choice, communication, and emotions.

Why not make use of it8?

Technology is required to move past the DSM

There is a paradigm shift underway in mental health research in which the classification system is transitioning away from DSM towards a new framework called the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC).

In 2013 the National Institute of Health (NIH) decided that the DSM was basically useless and stopped funding mental health research based on DSM categories.

Then director, Tom Insel wrote:

“While DSM has been described as a “Bible” for the field, it is, at best, a dictionary, creating a set of labels and defining each. The strength of each of the editions of DSM has been “reliability” – each edition has ensured that clinicians use the same terms in the same ways. The weakness is its lack of validity. Unlike our definitions of ischemic heart disease, lymphoma, or AIDS, the DSM diagnoses are based on a consensus about clusters of clinical symptoms, not any objective laboratory measure…

Patients with mental disorders deserve better. NIMH has launched the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project to transform diagnosis by incorporating genetics, imaging, cognitive science, and other levels of information to lay the foundation for a new classification system…

Here’s what’s happening:

DSM—>RDoC

Self-report surveys/structured interviews—>Digital Phenotyping

RDoC and Digital Phenotyping

Last year in Psychedelics & Digital Phenotyping, I wrote:

From Harvard's Digital Phenotyping and Beiwe Research website:

““What is digital phenotyping?” We define digital phenotyping as the “moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices, in particular smartphones.”

The critical takeaway is that digital phenotyping relies only on gathering data from regular interactions one has with their phone, such as swiping, typing, scrolling, speaking, etc. NOT the "active" answering survey questions or responding to prompts throughout the day.”

The collection and analysis of these data streams are required to move past the category-based framework of the DSM to an “alternative [with] a focus on psychopathology based on dimensions simultaneously defined by observable behavior (including quantitative measures of cognitive or affective behavior) and neurobiological measures9.”

This alternative is the RDoC.

The ‘Godfather’ of digital phenotyping, JP Onnela, and colleagues note in the journal Translational Psychiatry:

“Combining the RDoC framework with digital phenotyping offered from smartphones and other connected devices presents a unique opportunity for psychiatric research. Through incorporating the potential of these new digital technologies into RDoC framed clinical questions, psychiatry can now explore new dimensions of pathology largely inaccessible only a few years before.”

So, the future looks like this: sleep, activity, situation avoidance, energy, mood, attention, focus, lethargy, emotional valence (positive affect, negative affect), and other data points will be passively collected and analyzed.

The result of this process is information that can then inform diagnosis, treatment and personal health practices.

The optimistic take is that in the future we will be evaluating the effect of psilocybin and escitalopram on discrete dimensions objectively captured in order to understand the organism-wide response, not rely on self report surveys.

In other words the term depresion and the current way it is defined and diagnosed is under intense evolutionary pressure.

Digitally Equipped Psychedelic Research

So how might the results of future psychedelic clinical trials be informed with the advent of digital biomarkers and digital phenotyping?

We may soon find out.

Compass Pathways is in Phase II of COMP360 for Treatment-Resistant Depression. The primary outcome measure is the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, a clinician-rated scale based on the DSM schema.

But Compass is also employing digital phenotyping technology through a partnership with Mindstrong, a company founded by the above-mentioned Tom Insel, former director of the NIH who oversaw the transition away from the DSM and member of Compass’s Scientific Advisory Board.

I bet we see a similar situation when Compass publishes their Phase II data that we just saw with the psilocybin vs. escitalopram trial. The primary outcome, a DSM based measure, will fail to capture the “real” impact10 that data from digital biomarkers will show.

And then there are the crucial matters of privacy, surveillance, data ownership, and portability.

Along with the challenges of intellectual property and patent disputes, this is another domain that will be contentious.

This seems like an area for collaboration, open source and blockchain projects to create competitive technologies in which individuals own their data and know where and how it is being used11. Beiwe is an open-source digital phenotyping and analysis program from JP Onnela that researchers can use for this.

In closing, the prospect of psychedelic medicine is exciting in its own right. But I think it is so fascinating that the psychedelic renaissance is coming of age at a time when the measurement and classification systems of mental health conditions are under enormous evolutionary pressure and changing.

It really is a paradigm shift.

broadly speaking. This includes empathogens, entactogens, the “tripless” psychoplastogens, etc.

Technically, the conclusion is that no conclusions can be drawn. Or that psilocybin is at least no less effective than Escitalopram. Scientists can correct me here.

Prof Kevin McConway, Emeritus Professor of Applied Statistics, The Open University: "The trial was not large, involving only 59 patients, and in several ways, the results were rather inconclusive… The lack of statistical significance means that we can’t rule this possibility out."

Prof Guy Goodwin, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, University of Oxford: The present study is not a quantum leap: it is underpowered and does not prove that psilocybin is a better treatment than standard treatment with escitalopram for major depression.

Dr. James Rucker, Lead for the Psychedelic Trials Group @ King’s College London, NIHR Clinician Scientist Fellow, and Consultant Psychiatrist, The Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience (IoPPN), King’s College London: “It is possible that the study was not adequately powered to detect a difference, or that this represents a true finding that the treatments are equivalent in terms of patient-reported outcomes, when delivered in this context. This is important, because other trials have indicated very large effect sizes for psilocybin therapy and the interpretation of this by some is that psilocybin will be more effective than established treatments for depression."

A “bank shot” is when the ball hits the backboard before going through the hoop.

And structured interviews.

This is not meant to be a critique of researchers or validation processes from someone completely outside the field. I hope it doesn’t come across as such.

If people could compare their self-rating of these factors against objective data that would probably be really effective. Is anything like this out there?

The risks, ethical considerations, and incentive structures are under fierce debate. Add psychedelics to the mix, and the bioethicists among us have their work cut out for themselves.

I mean, regardless of whether it is clinically significant or not, the more sophisticated picture of the results will come from digitally captured datasets.

If you’re working on this, I would love to hear from you

Subscribe to The Trip Report by Beckley Waves

on the business, policy and science of psychedelics